History of Kumamoto Prefecture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

The history of Kumamoto Prefecture has been documented from paleolithic times to the present. Kumamoto Prefecture is the eastern half of Hinokuni (meaning "land of fire"), and corresponds to what was once called Higo Province. Exceptions are the parts of Kuma District, which had once been part of Sagara Domain, and Nagashima which was included in Kagoshima Prefecture.

Kumamoto Prefecture is roughly divided into three areas, namely, the northern area with Kikuchi River, Shirakawa River and Mount Aso Area; the Kumagawa Area including the Hitoyoshi Basin and the Amakusa Island Area. The first one is the Kumamoto han, and the second the Hitoyoshi han and the third one is the Amakusa Area, once controlled by the Tokugawa shogunate. The history of Kumamoto is characterized by kofuns in natural beauties or volcanic activities, the ritsuryō and the following rise of samurais, the arrival of Katō Kiyomasa from Nagoya, wars around the Bakumatsu including the Satsuma Rebellion, and public problems concerning Minamata disease. After the establishment of the Yamato Government or Yamato Ouken, the history of Kumamoto has been constantly under the influence of the Central Government.

Prehistoric Kumamoto

[edit]About one-third of the archaeological sites of the Lower Paleolithic age in Japan were found in Kumamoto Prefecture. A few of these have been excavated. Mainly these were in the outer Aso mountain areas and Kuma district. The oldest one is the Ishinomoto Site in Hirayama machi in Kumamoto City; dating back more than 30,000 years ago by the radiocarbon dating method. A large number of artifacts or stone tools such as stone axes and knives were excavated, suggesting that Kyūshū was inhabited by a number of hunter-gatherer societies.

At the same time, Kyūshū experienced volcanic activity at Mount Aso, Aira Caldera in Kagoshima Prefecture and Kikai Caldera. There were four large series of Mount Aso volcanic eruptions, with structural changes. The last one was about 90,000 years ago. The lava produced stone materials that would later be used for bridge construction in the Prefecture.

Jōmon period and Yayoi period

[edit]Jōmon period

[edit]There is little evidence of human activity in the early part of the Jōmon period in the Kumamoto Prefecture, because of volcanic activity about 7300 years ago by the Kikai Caldera in Kagoshima Prefecture. The Goryo midden and Kurohashi midden date to the middle age of the Jōmon period. Later, 13 middens in Kumamoto were situated at the height of 5 meters above sea level. In Souhata midden, stored acorns were found. Fish hooks made of stone were found in Amakusa. A peculiar style of earthenware called kokushokukenmadoki was developed according to the development of living styles. Burned rice corns and barley corns were found in a dugout (shelter) dwelling in Uenobaru midden in Kumamoto City.[1] 770 Archaeological sites were found in the Jōmon period in Kumamoto Prefecture, including Kannabe midden, Kumamoto in which Dogūs and ground stones were found.

Yayoi period

[edit]In the Yayoi period, there appeared dwellings in ring-formed groups in which onggis, tsubo jars, and stone axes were found. Dwellings rose into higher places, moving from the seashores. Cultivation and agriculture started in the Yayoi period, because the Kumamoto plane started to rise because of stream sediments from the rivers. Cultivation of rice started, while there were shell heaps along the seashore. Salt was produced by burning sea weeds; which has been verified by the presence of burned small seashells. In later years, there were middens with ironware along the Kurokawa river, Shirakawa river, and Kikuchigawa River and in the Futagozuka midden in Kumamoto City, suggesting the production of ironware there. In the Yayoi period, there were 740 middens in Kumamoto Prefecture, comprising 13% of middens in Japan. In the Tokuo midden and the Kogabaru midden, bronze mirrors were excavated.

Land of Fire

[edit]

In the Nihon Shoki, Japan's earliest official document, the early countries of Yamato Ouken, Wa (Japan), appointed a king of a small area which came under the Yamato Ouken, a head of Agata Nushi (an agata was an autonomous district under the leadership of a chieftain or warlord). Yamato Ouken is considered to be the forerunner of Japan's Imperial House of Japan existing in the Nara area or somewhere and started in the 3rd century. In the same document and in the Chikushi-koku-fudoki, there were three Agatas or Districts in the present Kumamoto Prefecture: Kuma agata, corresponding to Kuma Area; Asonken, corresponding to the Mount Aso area; and Yatsushiro area, which is considered to have been larger than today.

There are about 1,300 Kofuns in Kumamoto Prefecture, and comprise 24% of kofuns in the country. Near the Uto Peninsula area are about 120 large kofuns, or megalithic tombs or tumuli, constructed between the early 3rd century and early 7th century. In Kumamoto Prefecture, there is a concentrated distribution of decorated kofuns, in which various patterns were drawn, for instance, breasts of a woman in Chibusan kofun in Yamaga city. In another kofun in Uto city, the burial of a woman in her thirties was confirmed, suggesting the presence of miko, a "female shaman, spirit medium" who conveyed oracles from kami. A sword in a kofun named Etafunayama kofun had Chinese characters describing Emperor Yūryaku. Because of this, historian Wakatakeru has suggested that this area was under the control of Yamato Ouken. One of the gōzokus was named Takebe-no-Kimi, a family of samurai nature, who was given such a name by Yamato Ouken, and who was assumed to live near Kokai-Honmachi; in those days, near Takebe.

A group of kofuns at Nozu are considered to be the site of Hinokimi or the King of fire or possibly King of the Hi River. Hinokimi was considered to be a descendant of one who answered to Emperor Keikō. In the mythological period, Emperor Keikō in his journey for expanding the Yamato Ouken, saw unexplainable spots of moving fire, Shiranui, (In Japanese, literally "unknown fire") in the Ariake Sea, and a Gozoku in that land replied that he did not know the fire. Today, it can be seen only on one day or so, and it is an optical phenomenon on the horizon of seeing moving spots of fire caused by fishing boats through heated air layers. See also Shiranui (optical phenomenon).

In 527AD, the Iwai Rebellion in Fukuoka Prefecture was quelled by the Yamato court. The rebellion was named after its leader, Iwai, who is believed by historians to have been a powerful governor of Tsukushi. The rebellion was quelled by the Yamato court, and played an important part in the consolidation of early Japan. The eruption of Mount Aso was described in the Book of Sui, probably through the influence of Yamato Ouken.[2]

Explanation of Yamato Ōken

[edit]There are various Japanese names for a political/governmental organization present starting in the third century of kofun period in Kinki area of Japan, composed of several powerful families, with Ō (king) or Ōkimi (great king) as its center. These names include Yamato Chōtei (Court), Yamato Ōken, Wa Ōken, and Yamato Seiken. At the same time, there are views that the presence of smaller regional states should be respected. At the present time, Yamato Chōtei (Yamato Court) is employed in the textbooks censored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. There is a view that Chōtei (Court) should not be used before the 4th and 5th century. At the present time, Yamato Ōken is tentatively used here.

Higo and the Ritsuryo system

[edit]This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as This is very confusing. There is a lack of focus. Need to decide whether this describes a person, a history book, a place, a system of government, or what. And why Japanese terms MUST be used for common English feudal terms. (November 2011) |

The name Higo first appeared in the Nihon Shoki, the official history of Japan, in its description of a soldier who returned from the Tang empire in 696 AD after 33 years of captivity after the Battle of Baekgang; he was Mibu no Moroishi of Kohshi gun of Higo Province. In the same book, the construction of Kukuchi castle in preparation for a possible attack was described in 696. This castle is considered to be a storage place.[3] Under the ritsuryō system of Japan, a branch of the central government called Kokufu[clarification needed] was placed in areas under the influence of the central government. In Kumamoto Prefecture, the Kokufu was placed in Mashiki, according to the Wamyō Ruijushō, and in other places according to other books. As the name of the place, Kokubu was in Kumamoto city, and there was a building in the 9th century; which was found destroyed in a flood. As a government post, Higonokami Michinokimi Obina was recorded; he was born in 663, and he assumed the post of the head of Higo Province. He was also a poet and his name was in Kaifūsō. As the heads of Higo Province, there were Ki Natsui, Fujiwaha Yasumasa and Kiyohara no Motosuke; the last one was a nobleman, waka poet, and the father of Sei Shōnagon who wrote The Pillow Book. Unlike other governors, Kiyohara went to Kumamoto. The ritsuryō system was introduced in the Asuka period, and silk was transferred to the capital for taxation. This was confirmed in the Wamyō Ruijushō and in the Shoku Nihongi. Fish and rice were also items for taxation and Higo was a big country in this respect. Division of land by roads was started and a transportation infrastructure, with stations, was prepared. Kokai Station was found within the campus of Kumamoto University.[citation needed][4]

White turtles

[edit]In 768, a white turtle was presented to Yamato Ouken from Ashikita, and in 771, two white turtles were presented from Ashikita, and Mashiki, both from Kumamoto coinciding with the enthronement of Emperor Kōnin, and the death of Empress Kōken, and the title of the years was changed from Jingokeiun to Hōki, meaning a precious turtle. Dōkyō, the lover of Empress Kōken lost power. At the same time, those under the influence of Fujiwara clan gained power among Kumamoto people over those under the influence of Ohtomo family.

The rise of the Samurai

[edit]In the latter part of the Heian period, groups of samurai gained power. This was also so in the land of Higo, though unification was not achieved until the 16th century. Well known groups of samurai included the Kikuchi clan, Aso clan, Kihara of the Midorigawa area, Moroshima of Amakusa, Sagara clan of Hitoyoshi, and Kumabe; some of them fought in the Toi invasion of 1019.

Kikuchi Clan

[edit]The Kikuchi clan started with Fujiwara Noritaka, grandson of Fujiwara no Takaie, who fought in the Toi invasion. However, at present, there are several views concerning its origin; 1) Local Gōzoku who worked at Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, 2) A descendant of Kishitsu Fukunobu from Korea, 3) A descendant of the Kukuchi family, 4) A descendant from the Minamoto clan. The Kikuchi clan enjoyed a powerful presence in the Kikuchi area, belonging to the group in the center of Japan by maintaining their land in the shōen system. In the days when the Taira clan was in power, the Kikuchi clan approached the Taira clan, but then the Minamoto clan came to power, and the Kikuchi favored the Minamoto. In the Kamakura period, the Kikuchi clan fought successfully against the enemy at Fukuoka during the Mongol invasions of Japan. Kikuchi Taketoki (1292–1333) was the 12th head of the Kikuchi Clan. Emperor Go-Daigo asked Taketoki for help. He was Go-Daigo's first man and was awarded for this. Taketoki gathered many people in Kyūshū and planned to attack Chinzei Tandai's Hōjō Hidetoki (Akahashi Hidetoki), but the plan was discovered and the Hojo attacked first. Taketoki and his son Yoritaka died in this attack. However, the Kikuchi clan remained powerful in this area.

Aso Clan

[edit]The Aso clan started with Kannushi worshiping the kami of Mount Aso area and later became the head of the Agata by presenting their land to the Yamato Ouken and later to the group in power as an organized manor (shōen). They became a powerful group of samurai, and they named themselves a Dai-guji, or great Kannushi and the top of gōzokus or samurai combined. It is said that Aso Shrine was the earliest shrine in Higo Province and included lower shrines such as Kengun Shrine in Kumamoto, Kosa Shrine, and Kouriura Shrine which extended the area of influence.

The formation of Samurai groups

[edit]Legend of Minamoto no Tametomo

[edit]In the latter half of the Heian period, samurai had waged wars in almost all areas of Japan, and Shirakawa Jokyo in cloistered rule started to control kokushis; the situation became very complex. In Kyūshū, Minamoto no Tametomo, a hero from Kyoto, was the subject of a number of legends. The legend of Minamoto no Tamotomo was interpreted as the uprising of groups of samurai in rural or peripheral areas of Japan against the previously authoritative groups of samurai. When Taira no Kiyomori had power, smaller groups of samurai had to choose either to side with the Heike clan or resist. The Rebellion of Chinzei was recorded in the Azuma Kagami, The Tale of the Heike, Genpei Jōsuiki, and it coincided with the uprising of Minamoto no Yoritomo. Defeated, their groups were incorporated within the Heike clan.

Kamakura Shogunate and Mongol invasions of Japan

[edit]The Kamakura period covers 1185 to 1333. Samurais in east Japan occupied the post of Soujitou, and the Kikuchi clan sided with Gotoba-joko, and lost to some extent. In 1268 and 1271, the Kamakura shogunate rejected the proposal of envoys from Mongol for peace. It ordered all those who held fiefs in Kyūshū to resist any Mongol Invasions. Fortunately Takezaki Suenaga left vivid pictures concerning the Mongol invasions of Japan.

Takezaki Suenaga

[edit]

Takezaki Suenaga (1246–1314) was a retainer of Higo Province who fought in both campaigns against the Mongols. Suenaga commissioned the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, a pictorial scroll showing his own valor in war, composed in 1293. During the Mongol invasion of 1274. Suenaga fought at Fukuoka under Muto Kagesuke. Suenaga sold his horses and saddles in order to finance a trip to Kamakura, where he reported his deeds in battle to the shogunate. In order to receive rewards for valorous deeds from the bakufu,[clarification needed] it was necessary for the deeds to be witnessed by others and reported directly. By his own account in the scrolls, Suenaga says, "Other than advancing and having my deeds known, I have nothing else to live for", showing that, first, he wanted to advance in terms of measurable money and rank, and that, just as importantly, he sought fame and recognition.

Muromachi period

[edit]The Muromachi period is subdivided into the Nanboku-chō period and the Sengoku period.

Nanboku-chō period

[edit]Nanboku-chō period is between 1336 and 1392. Emperor Go-Daigo started to overthrow the shogunate Hōjō Takatoki and the order to join in the revolt was given by Prince Kanenaga (or Prince Kaneyoshi) to various samurai groups in Kyūshū. Kikuchi Taketoki was killed in a battle in Fukuoka. The Kikuchi and Aso clans sided with the Southern Court in Kyoto. Later, the Northern Court won over the Southern Court. In order to strengthen the Kikuchi clan, Kikuchi Takeshige was made Yoriaishu Naidan no Koto in 1338, meaning the rules of decision within the Kikuchi clan were made with blood signature. This was translated into the Kikuchi Constitution, the oldest blood signature, and this was stored in the Kikuchi Shrine.

Muromachi period

[edit]Shibukawa Mitsuyori assumed the Kyūshū branch of central government, Kyūshū Tandai, the military branch of the Ashikaga shogunate. The Kikuchi clan initially resisted, however, it approached the Ashikaga shogunate later. The Kikuchi clan started to trade with Korea and gained some strength. In 1481, a large meeting for "10,000 Renga" (collaborative poetry) was held in Kikuchi, the land of the Kikuchi clan, thus showing high standards of culture was there. Later the Kikuchi clan declined. Sagara families fought within their own families in Hitoyoshi area, but stayed there because the Hitoyoshi area is encircled by mountains. Aso families staged conflicts within their families in the Aso area.

Sengoku period

[edit]The Sengoku period is roughly between 1467 and 1572. The Kikuchi clan declined, and Higo Province became the land of Field Mowing, meaning that the strong could take the land of the weaker.

Azuchi-Momoyama period

[edit]Azuchi–Momoyama period was from 1573 to 1603. It was followed by the Edo period.

Sassa Narimasa

[edit]

In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi started to invade Kyūshū in his war to unify Japan and reached Kumamoto on April 16. He gave letters of reassurance of the possession of land to 52 persons in Kumamoto, and gave Sassa Narimasa the Province of Higo. Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered that the measurements of land should not be examined in the following three years. However, Sassa Narimasa could not observe the order and conflict started; Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered the groups of samurai in Higo be destroyed. Sassa Narimasa was responsible for this conflict and he was ordered to commit seppuku. On the following day, Toyotomi Hideyoshi gave the northern half of Higo Province to Katō Kiyomasa and the southern half to Konishi Yukinaga. Sagara clan in Hitoyoshi lost Yatsushiro and Ashikita, but finally the possession of Hitoyoshi was reassured. Five groups of samurai in Amakusa resisted Konishi Yukinaga, but were finally defeated.

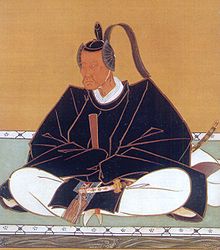

Katō Kiyomasa

[edit]

The decisive Battle of Sekigahara (October 21, 1600) cleared the path to the Shogunate for Tokugawa Ieyasu. In Kyūshū, Katō Kiyomasa, and other samurai lords such as Kuroda, Nabeshima, Hosokawa took the side of Tokugawa Ieyasu; while Konishi Yukinawa, Shimazu, Ōtomo, Tachibana acted on behalf of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Katō Kiyomasa attacked Uto Castle, and he won the battle when the news of the defeat of Ishida and the capital punishment and defeat of Konishi Yukinaga reached Uto. Katō Kiyomasa was given the province of Higo with the exception of Hitoyoshi and Amakusa. His rice income reached 540,000 koku (bales of rice) and he was asked to add his followers, and accepted the previous samurai belonging to Konishi Yukinaga and Tachibana. He started to strengthen Kumamoto Castle and completed it in 1607. Kiyomasa was one of the three senior commanders during the Seven-Year War (1592–1598) against the Korean dynasty of Joseon. Together with Konishi Yukinaga, he captured Seoul, Busan and many other crucial cities. He defeated the last Korean regulars in the Battle of Imjin River and pacified Hamgyong.

Some Korean artisans were taken to Kumamoto by Kiyomasa. A town named Ulsan (Urusan) is in Kumamoto now. Kato shrine is a shrine in Kumamoto Castle, Kumamoto, in which Katō Kiyomasa, Ōki Kaneyoshi and Kin Kan, a Korean who followed Katō, are enshrined.

Kiyomasa was an excellent architect of castles and fortification. During the Imjin war, he built several Japanese style castles in Korea to better defend the conquered lands. Ulsan castle was one of these fortresses that Kiyomasa built, and it proved its worth when Korean-Chinese allied forces attacked it with far superior force, yet the outnumbered Japanese successfully defended the castle until the Japanese reinforcements arrived. After the meeting of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori, he became ill on a ship on his way to Kumamoto, and died shortly after arrival in 1611. His child, Katō Tadahiro, was transferred to Dewa Maruoka-han in the Tōhoku region in 1632, for fear of his becoming too powerful and thus the Kato clan came to an end.

Hosokawa Clan

[edit]Hosokawa Tadatoshi of the Hosokawa clan entered Higo Province in 1632; he declared that he respected Katō Kiyomasa. Retired Hosokawa Tadaoki entered Yatsushiro castle. Hosokawa Tadatoshi introduced the system of tenaga, which was larger than a village; this system had been observed in his previous Han. The top of a tenaga was originally by heritage, but later the head of a tenaga was appointed from above. It was a bureaucracy, but a more suitable system than heritage alone.

Christianity

[edit]Catholic culture and Amakusa

[edit]Amakusa

天草市 | |

|---|---|

City | |

Location of Amakusa in Kumamoto | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kyūshū |

| Prefecture | Kumamoto |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (JST) |

Top, from left to right: Julião Nakaura, Father Mesquita, Mancio Ito.

Bottom, from left to right: Martinão Hara, Miguel Chijiwa.

Katō Kiyomasa was an earnest Nichiren sect Buddhist, and did not like Christians. He proposed that Amakusa and Tsurusaki (Ōita Prefecture) be exchanged[clarification needed] when he obtained the land of Kumamoto, and this was realized. Gōzoku in Amaksa repeatedly fought each other in the Sengoku period. In 1560, they realized the superiority of the arquebus which Matsuura Takanobu had introduced into local warfare.

In 1566, a gōzoku asked Cosme de Torrès to send a Catholic missionary. Luís de Almeida was dispatched in the same year. He built a church with the permission of the rulers. In 1568, a congress of foreign missionaries was held in Amakusa. In 1570, missionaries baptized the Shiki, Amakusa, and Amakusa ruling families. In Amakusa, five jizamurai also became Christian.

As a result, Catholic culture flourished. Amakusa College (College Amacusa) graduated scholars between 1591 and 1597, at Hondo or Kawaura of Amakusa.[5] It published more than twelve books including Aesop's Fables in Japanese in 1593 and the Tale of the Heike (Feique No Monogatari), in 1592, with the Gutenberg press, imported from Italy by overseas scholars Itō Mansho (Mancio Itō), Miguel Chijiwa, Hara Maruchino, and Nakaura Julian. Upon returning, they continued their studies at Amakusa College.[6]

The number of Christians in Amakusa was great, more than a half of inhabitants, 9,000–11,000 (1580) or 23,000 (1592) were documented. After the martyrdom of 26 saints at Nagasaki and the prohibition of Christianity, the printing machine was transferred to Nagasaki.[7]

Shimabara Rebellion

[edit]The Shimabara Rebellion was an uprising largely involving Japanese peasants, most of them Catholic Christians, in 1637 and 1638. In the wake of the Matsukura clan's construction of a new castle at Shimabara, taxes were drastically raised, which provoked anger from local peasants and lordless samurai (rōnin). In addition, religious persecution against the local Christians exacerbated their discontent, which turned into open revolt in 1637. The Tokugawa shogunate sent a force of over 125,000 men and defeated them. The rebel leader Amakusa Shiro, a charismatic 15-year-old Christian, died when the castle fell. Executed in the aftermath of the fall, his head was displayed on a pike in Nagasaki for a long time afterward as a warning to any other potential Christian rebels. Persecution of Christianity was strictly enforced. Japan's national seclusion policy was tightened, and formal persecution of Christianity continued until the 1850s. In 1641, Amakusa was put under the direct control of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Hidden Christians in Amakusa

[edit]

In 1805, 5,200 underground "hidden" Christians were found in Amakusa. The Tokugawa shogunate treated this problem with unexpected leniency and recognized religious conversion.

Amakusa and Christianity in later years

[edit]People in Amakusa heard that the ban on Christianity had been lifted and some people reported that their faith was converted to Christianity in 1876. However, it was not accepted, and some others were punished because they conducted funerals according to the Christian style. In 1892, a French father, Frédéric Louis Garnier (1860–1941), started a church in Oe, Amakusa.[8]

Edo period

[edit]The town area of Kumamoto had been completed at the time of Katō Kiyomasa. Tsuboi Kawa (river) had been separated from the Shirakawa. Portions of Tsuboi Kawa and Iseri Kawa were made into moats of Kumamoto Castle. Samurai residential areas were placed around Kumamoto Castle, and the areas for townspeople were separated. Choroku Bridge was the only bridge crossing the Shirakawa (river); it was the only one for the defense of Kumamoto Castle. Suizenji Park, a Japanese style garden, was made for the exclusive use of the Hosokawa clan in 1634. A factory for wax production was completed in 1803; the products were transported over the rivers to the sea.

Temples had been burnt in the Sengoku period, especially those in the Mount Aso area, but some were later reconstructed. In those areas, hot spring sites were constructed between 1804 and 1829 in Kurokawa and Yamaga. Sake production flourished.

Uto castle was once destroyed, but it was rebuilt and there was water supply service, which works even today. Although Higo (Kumamoto and Yatsushiro) was then one domain, Yatsushiro Castle was made a single exception to the rule of one castle in one domain; because there was need to defend Kumamoto against the powerful Satsuma Han to the south and to defend Japan from foreign invasion.

Katō Kiyomasa and the Hosokawa clan increased the productivity of Kumamoto han by various means, such as the control of rivers and land reclamation by drainage on the sea. One example was the construction of Tsūjun Bridge which made barren land fertile land.

Hitoyoshi enjoyed the status of a separated han, and there was a special taxation system; various items were available for taxation products in addition to rice, and they were transported via the Kuma River. In Amakusa, Suzuki Shigenari was the head of the regional branch of the Tokugawa shogunate and governed Amakusa, and he repeatedly asked the shogunate for the reduction of rice taxation, from 42,000 koku to 21,000 koku. He committed ritual suicide (seppuku) to achieve this reduction successfully, though there was a view that he died through disease.

Horeki Reform

[edit]

Hosokawa Shigekata (January 23, 1721 – November 27, 1785) was the 6th lord of Kumamoto, of the Hosokawa clan, and noted for his successful financial reform of the Kumamoto Domain. His elder brother, the 5th daimyō, unfortunately and unexpectedly was killed, and so Shigekata had to face the financial difficulties of the Kumamoto Han. The deficit at the time of his father reached 400,000 ryō. The finance of his Han had worsened because of the policy of the Tokugawa shogunate which required the sankin-kotai, a policy where a daimyō had to spend alternating years in the city of Edo. This policy was a great financial burden for a daimyō, who had to pay for travel to the capital in a manner befitting his status, and had to maintain an appropriate residence in the capital and in his domain.

In 1752, Shigekata appointed Hori Katsuna to the post of "great bugyō". Hori immediately went to Osaka to negotiate with Kohnoike family and others for loans, but the wealthy families refused the request. Then, Hori was successful in borrowing a huge sum of money from Kajimaya in return for the 100,000 koku of rice from Kumamoto Han. Kajimaya requested a considerably reduced financial policy of Kumamoto han. The Kokudaka or the system of koku refers to a system for determining land value for tribute purposes in the Edo period Japan and expressing this value in koku of rice. This tribute was no longer the percentage of the actual quantity of rice harvested, but was assessed based on the quality and size of the land. The system was used to value the incomes of daimyōs, or samurai under daimyōs. Originally, the samurai kept 40% of all rice produced. After the reform, 20 koku per 100 went to a samurai, and then 13 koku, this meant a reduction of 65%.

Education, commercial, and criminal law reform

[edit]Kumamoto han wanted the samurai to be satisfied with the Hōreki reforms, and at the same time, they should train themselves as strong warriors. One way to meet this goal was to build a school for samurai and others. Another idea was to rehabilitate those who went against the rules, and Shigekata created a completely new criminal law. He also started a medical school called Saishunkan. In addition, Shigekata and Hori started various new industries involving Japanese paper, silk, and wax.

Famine and tsunami

[edit]In 1634, there was a considerable famine which may have contributed to the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637. The reduced production of rice was observed occasionally from time to time; 1729 was also the year of famine, and it was recorded that there was only 11% of the mean annual production. In addition to famine, there was a peculiar tsunami. In 1792, a large mountain, Mayu Yama (Maeyama), at the foot of the volcano Mt. Unzen (Nagasaki Prefecture) collapsed with volcanic earthquakes, produced a great tsunami that struck the seashore of Kumamoto Prefecture. In all, 15,000 people died. This was the second largest tsunami in the history of Japan, after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.

.

Farmers' uprisings

[edit]Usually translated as peasant uprising, it was reported that wealthy farmers also participated; in Higo Province, more than 100 cases of farmers' uprisings were recorded. These cases were characterized by small numbers of participants, less than 300 people, and their claims were the reduction of taxation, about the instability of han money, request for the resignation of the shoya and employees. In 1747, farmer uprising occurred in Ashikita, requesting the withdrawal of the resignation of Inatsu Yaemon, a high-ranking official who had an understanding of farmers. Its participants numbered 7,000 to 8,000 people.

19th Century

[edit]Yokoi Shonan and the Bakumatsu

[edit]

The Bakumatsu was a period toward the end of Tokugawa shogunate. Yokoi Shōnan (1809–1869) was a scholar and political reformer in Japan, influential around the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate. Yokoi was a samurai born in Kumamoto, was sent by the domain to Edo in 1839 for studies, and developed contacts with pro-reform members of Mito Domain. After his return to Kumamoto, he started a group to promote the reform of domain administration along Neo-Confucian lines. In 1857, he was invited by the daimyō of Echizen, Matsudaira Yoshinaga, to become his political adviser. Although he was highly evaluated at that time, he was assassinated in 1869.

Meiji Restoration

[edit]

There was a chain of events from the Bakumatsu, Meiji Restoration (1868), Abolition of the han system (1871) and Satsuma Rebellion (1877). The name of the Prefecture was finally made Kumamoto Prefecture in 1876.

The Sword Abolition Edict and the abolition of the caste system were issued in 1876, and samurai were angered and became furious. Saigō Takamori, the hero and leader of Meiji Restoration, left the central Meiji Government and returned to Kagoshima, with disaffected samurai followers.

Satsuma Rebellion

[edit]In 1877, the Satsuma army came to Kumamoto, but languished for two months during the Siege of Kumamoto Castle, which proved the unrivaled durability of the castle. Shortly before their attack on Kumamoto Castle, the surrounding townscape was burned in preparation for the battle. Kumamoto Castle also burned down, though the cause of the fire is unknown. The commander of Kumamoto Castle was Tani Tateki who was fresh from the Taiwan Expedition of 1874.

In 1877, Sano Tsunetami (1823–1902) created the Hakuaisha, a relief organization to provide medical assistance to soldiers wounded in the Satsuma Rebellion. This organization became the Japanese Red Cross Society in 1887, with Sano as its first president.

Souha Hatono VIII of Kumamoto (1844–1917) was a Japanese physician. During the Satsuma Rebellion, he treated wounded soldiers from both sides equally. He faced a trial for trying to benefit the enemy, but was proved innocent. His activities were in accord with the spirit of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Modernization

[edit]Imperial Army

[edit]Chinzei Tandai, one of the six large units of the Japanese Army, was placed in Kumamoto in 1871. After the Satsuma rebellion in 1877, the 6th Infantry Division was formed in Kumamoto City on May 12, 1888, as one of the new divisions to be created after the reorganization of the Imperial Japanese Army away from six regional commands and into a divisional command structure. The headquarters were placed in Kumamoto Castle, with the infantry battalion, the cavalry battalion and artillery battalion, and this arrangement came to an end at the end of World War II. Japan experienced the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894. After the Russo-Japanese War, Kumamoto accepted about 5,000 prisoners of war at Toroku. A large-scale military exercise was held in Kumamoto, attended by Emperor Hirohito, 1931.

To Prosperous Kumamoto

[edit]The army's Yamasaki Training Area, placed after the Satsuma Rebellion, blocked traffic and the development of Kumamoto City. In consideration of public opinion, other military buildings were transferred to Toroku and Oe Mura, but the Yamasaki Training place was still there. At the cost of Kumamoto City, it moved to Oe Mura, starting as late as 1898. In the wake of the Yamasaki Training place, Renpei Cho and Karashima (then mayor) Cho were named, and Shinshigai became the busiest section of Kumamoto City. In 1907, Kumamoto Light railway company started, which later changed to Kumamoto Electric Railway Company and then to streetcars. Public organizations were invited, such as the 5th Higher Middle School in 1887 which changed to the 5th High School in 1894, Tobacco Monopoly Bureau in 1911. Infrastructure such as construction of roads, water supply (1924), streetcar lines were completed, which was the basis of development for Kumamoto City.

Disasters

[edit]Near the end of World War II, Kumamto experienced several air raids, and the greatest one on the night of June 30 to July 1, 1945. About one third of the city was burned, and more than 300 people died. After the war, there were a considerable number of floods due to typhoons, possibly exacerbated by deforestation and delay in river control. In June 1953, there was a combination of Mount Aso eruption and floods, causing debris to flow into the center of Kumamoto city, and more than 500 people died in Kumamoto Prefecture.

Various dams, such as Ichifusa dam, Midorikawa dam, Ryumon dam, have been constructed to prevent another disaster. Tateno dam is under construction.

The 1973 Taiyo Department Store fire occurred in the center of Kumamoto City. The fire started at 1:15 pm on November 29, 1973; and 103 people died. After the fire, national regulations pertaining to the construction of buildings were strengthened, one of which was the building of external steps outside of the high-storied buildings.

Industry

[edit]Since early times agriculture has remained an important industry. In 1911, the government encouraged agriculture by placing agricultural experiment stations in Kumamoto Prefecture. Since 1964, industrialization started, with factories for the production of motorcycles and semiconductors. Kumamoto Technopolis Project was started to invite various factories near Kumamoto Airport. The Five Bridges of Amakusa linked the Kyūshū mainland and the Amakusa Islands, and opened on September 24, 1966. The Five Bridges not only gave hope and confidence in the development of Japan's bridge construction technology, but also changed many aspects of life in the Amakusa Islands. Mount Aso and Amakusa became sightseeing destinations.

Minamata disease

[edit]

The Chisso Corporation (チッソ株式会社, Chisso kabushiki kaisha) started a factory in Minamata city in 1908. In 1956 that Minamata disease was identified and described; it was caused by the release of methylmercury in the industrial wastewater from the factory. The symptoms of the disease include ataxia, numbness in the hands and feet, general muscle weakness, narrowing of the field of vision, and damage to hearing and speech capability. As of March 2001, 2,265 victims were officially recognised (1,784 of whom had died) and over 10,000 received financial compensation from Chisso. By 2004, Chisso Corporation had paid $86 million in compensation. On March 29, 2010, a settlement was reached to compensate as-yet uncertified victims.

Foreign advisors in Kumamoto Prefecture

[edit]

Koizumi Yakumo(小泉八雲)

- Hannah Riddell: (1855–1932) Englishwoman who established Kumamoto's first leprosarium, the Kaishun Hospital, in 1895.

- Ada Hannah Wright: (1870–1950) Englishwoman, director (1932–1941) of Kaishun Hospital.

- Lafcadio Hearn: also known as Koizumi Yakumo, (1850–1904); international writer, best known collections of Japanese legends and ghost stories, such as Kwaidan; worked at Kumamoto University.

- Father Jean Marie Corre: French pries who established a leprosarium, Tairoin Hospital, in 1898.

- Marie Colombe de Jesuis, Marie Beata de Immaculee Conception, Marie de la Purete, Marie Annick and Marie Trifine: nuns who volunteered to work at Tairoin Hospital.

- Leroy Lansing Janes (1837–1909) was an American Army officer. Also, taught English to Japanese pupils at Yoh Gakkou, Kumamoto, without interpreter. His subjects included English, English writing, literature, mathematics, physics, chemistry and history. In 1876, he taught Christianity to 30 pupils, and his school was abolished.

- Constant George van Mansvelt (1832–1912) was a Dutch physician who taught medicine at Nagasaki in 1866 and in Kumamoto (Kojo Medical School) between 1871 and 1873. One Kumamoto student was Kitasato Shibasaburō. In 1876, he taught medicine in Kyoto Prefectural Hospital. In 1877, he moved to Osaka Hospital and in 1879, he returned to Leeuwarden. He died in 1912 at age 80. He lectured every subject of medicine.[9]

References

[edit]- Matsumoto J, Itakusu K, Kudou K, Igai T: History of Kumamoto Prefecture Yamakawa Shuppansha 1999, ISBN 4-634-32430-X

- Matsumoto J, Yoshimura T: History of Japanese Gaido; The Land of Hi(fire) and Sea of Shiranui Yoshikawa Koubunkan, 2005, ISBN 4-642-06251-3

- Kumamoto-ken High-School Shakaika-Kenkyuukai Kumamotoken no Rekishisanpo, Yamakawa Shuppansha, 2002, ISBN 4-634-29430-3

- Iwamoto C et al. History of Kumamoto in Topics Gen Shobou, 2007, ISBN 978-4-902116-85-4

- Glossary of Japanese history

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The History of Kumamoto City Archived June 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ History of Aso Faith by Aso Sogen Saisei Kyogikai

- ^ Why was Kukuchi Castle built ? Kikukamachi Kankyo Kyokai Archived February 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kokai Station is within the campus of Kumamoto University, as described in the Home Page of Kumamoto University.

- ^ Which one is correct remains undecided

- ^ The book of the Aesoop's Fables was reprinted in Japanese ESOPO by Tetsuko Nakagawa ISBN 978-4-87755-351-7 Kumamoto Nichinichi Shimbun, 2009

- ^ Iwamoto C. et al. History of Kumamoto in topics Gen Shobou, 2007, p98–99

- ^ He was mentioned in 5 Pairs of Shoes by Yosano Tekkan, Mokutaro Kinoshita, Kitahara Hakushu, Hirano Banri and Yoshii Isamu

- ^ Souta H. Modernization of Medicine and Doctors who came to Japan Sekai Hoken Tsuushinsha 1988 ISBN 4-88114-607-6 p29.